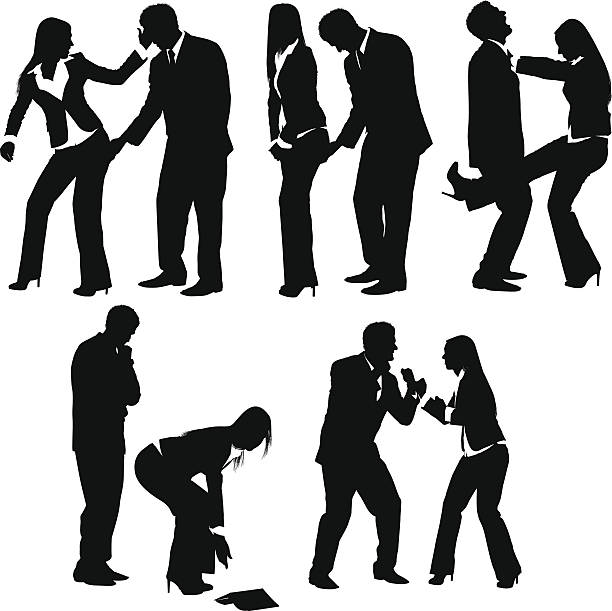

Sexual Harassment and Harassment, What’s the Difference?, is an important technical consideration in your decision making a decision how to proceed. Any form of harassment in the workplace is unlawful and employees have the right to complaint or lodge a claim regarding the harassment they are experiencing. However, it is important to distinguish between the different forms of harassment and how each one can be dealt with.

Harassment, which is sexual in nature, is referred to as “Sexual Harassment”. Sexual harassment, as defined under Federal and State specific anti-discrimination laws, is unwanted or unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors or conduct of a sexual nature in circumstances which a reasonable person, having regard to all the circumstances, would have anticipated this behaviour to cause offense, humiliation or intimidation.

Although sexual harassment is defined under Federal and State specific anti-discrimination laws,

the essential elements to satisfy the legal test is:

- The behaviour must be unwelcome.

- The behaviour must be of a sexual nature.

- The behaviour must be such that a reasonable person would anticipate in the circumstances that the person who was harassed would be offended, humiliated and/or intimidated.

Whether the behaviour is unwelcome is a subjective test. This means that the conduct in question is examined in relation to how it was perceived and experienced by the complainant and this is of greater importance rather than the intention behind it. Furthermore, the unwelcome behaviour need not be repeated or continuous. A single isolated incident can amount to sexual harassment.

Whether the behaviour was offensive, humiliating or intimidating is an objective test and considers whether a reasonable person would have anticipated that the behaviour would have this effect.

Given this legal test, examples of sexual harassment involve unwelcome touching, hugging or kissing; sexually suggestive comments or jokes; sexually explicit messages, pictures or illustration; unwanted invitations to go out on dates; unwanted and unwelcome requests for sex or sexual favors; intrusive questions about your private life, sex life or body; accessing sexually explicit internet sites or any other behaviour which would also be an offence under the criminal law, such as physical assault, indecent exposure, sexual assault, stalking or obscene communications.

Harassment Which is Not Sexual – Workplace Bullying

The Cambridge English Dictionary defines general “harassment” as “illegal behaviour towards a person that causes mental or emotional suffering, which includes repeated unwanted contacts without a reasonable purpose, insults, threats, touching, or offensive language”. Harassment in this general sense is not explicitly defined in our industrial relations or employment laws but its dictionary definition aligns with the meaning of “workplace bullying” under the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth).

Under s.789FD(1) of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth), “workplace bullying” occurs when an individual or group of individuals repeatedly behaves unreasonably towards a worker or a group of workers at work and the behaviour creates a risk to health and safety. Thus, to satisfy the first part of this legal test, the behaviour needs to be repeated and cannot be an isolated incident, which differs from the definition of sexual harassment where a single isolated incident can amount to sexual harassment. A anti bullying, or anti sexual harassment complaint can be lodged at the Fair work Commission. (Form 72)

The behaviour also needs to be deemed “unreasonable” under an objective assessment of the action. This objective test is similar to the objective test required to satisfy one element of the legal test of sexual harassment, being whether the conduct is offensive, humiliating or intimidating. In order to satisfy the second part of the legal test, the action must create a risk to health and safety. A risk to health and safety means the possibility of danger to health and safety and is not confined to actual danger to health and safety.[1] The ordinary meaning of ‘risk’ is exposure to the chance of injury or loss[2] and the risk must be real and not simply conceptual.[3]

Fair work Commission’s role

With this legal definition in mind, examples of bullying behaviour was provided by the Fair Work Commission in Amie Mac v Bank of Queensland Limited and Others.[4] The Fair Work Commission held that some of the features which might be expected to be found in a course of repeated unreasonable behaviour constituting bullying at work were “intimidation, coercion, threats, humiliation, shouting, sarcasm, victimisation, terrorizing, singling-out, malicious pranks, physical abuse, verbal abuse, emotional abuse, belittling, bad faith, harassment, conspiracy to harm, ganging-up, isolation, freezing-out, ostracism, innuendo, rumor – mongering, disrespect, mobbing, mocking, victim-blaming and discrimination”. [5]

Jurisdictions outside the Fair Work Commission have held that bullying behaviour can also include aggressive and intimidating conduct,[6] belittling or humiliating comments,[7] victimisation,[8] spreading malicious rumors,[9] practical jokes or initiation,[10] exclusion from work-related events,[11] and unreasonable work expectations.[12]

Defences for Harassment Complaints

Disproving workplace bullying claims (harassment complaints by general definition) requires an employer to demonstrate that the alleged bullying behaviour is in fact reasonable management action, which does not constitute workplace bullying. The Fair Work Commission has held that management action constitutes performance appraisals,[13] ongoing meetings to address underperformance,[14] counselling or disciplining a worker for misconduct,[15] modifying a worker’s duties including by transferring or re-deploying the worker,[16] investigating alleged misconduct,[17] denying a worker a benefit in relation to their employment,[18] or refusing an employee permission to return to work due to a medical condition.[19]

The question of what management action above is reasonable, is an objective test.[20] Whether the management action was taken in a reasonable manner will depend on the action, the facts and circumstances giving rise to the requirement for action, the way in which the action impacts upon the worker and the circumstances in which the action was implemented and any other relevant matters.[21] Thus, the employee must be able to demonstrate that the decision to take management action lacked any evident and intelligible justification such that it would be considered by a reasonable person to be unreasonable in all the circumstances.[22] This requirement makes workplace bullying complaints increasingly difficult.

Defences for Sexual Harassment Complaints

In order to disprove a claim of sexual harassment against an individual, a person will need to demonstrate that that the conduct is sexual interaction, flirtation, attraction or friendship which is invited, mutual, consensual or reciprocated. Although an individual may argue that the conduct is not sexual harassment because it appears to be mutual, it is important to examine a number of surrounding circumstances, including withdrawn consent and power imbalances.

If a relationship between employees began in a mutual and consensual manner, this constitutes consent and thus does not constitute sexual harassment. However, if this consent is withdrawn or no longer invited and mutual, such as one employee wants the relationship to end and the other party does not agree, this may constitute sexual harassment.

In addition, any power imbalance between the individuals may render a seemingly consensual relationships in the workplace as unwelcome conduct which amounts to sexual harassment. The Courts have taken into account the power imbalance between the parties when considering whether there has been sexual harassment, and in determining damages.

Although a party may not indicate certain conduct is unwelcome, a failure by the complainant to challenge each incident of unwelcome conduct does not unequivocally amount to acceptance of that conduct. It is well recognised by the Courts that a complainant may remain silent in the face of sexually unwelcome conduct for a number of legitimate reasons.

Unwelcome advances

For instance, a junior staff member is subject to unwelcome advances or other conduct by their boss or a more senior staff member but does not speak up or indicate this conduct is unwelcome. Despite their silence, the conduct can still be deemed sexual harassment as the employee’s apparent consent to engage in the conduct is only out of fear of reprisal or fear for job security. The more significant the power imbalance, the higher the general and aggravated damages awarded.

These defenses are relevant if you are making your claim against the individual employee who has subjected you to the sexual harassment. An employee may also name their employer as a Respondent to their sexual harassment complaint, under vicarious liability. Employers have a responsibility to take all reasonable steps to prevent sexual harassment in employment, such as implementing a sexual harassment policy and providing training or information on sexual harassment. Thus, an employer’s first defense may be to demonstrate that the conduct in question is not sexual harassment by definition. If this defense fails, the employer can then argue that they have taken all reasonable steps to minimize the risk of discrimination and harassment occurring.

Although this is not defined, whether an employer has taken all reasonable steps is determined on a case-by-case basis depending on the size and available resources of the employer in questions. The employer would be expected to demonstrate they have an appropriate sexual harassment policy, demonstrate that they train employees on how to identify and deal with sexual harassment, demonstrate their internal procedure for dealing with complaints and demonstrate that they have taken appropriate remedial action if and when sexual harassment occurs.

Sexual Harassment and Harassment, What’s the Difference?, How Can We Help?

Are you experiencing harassment or sexual harassment in the workplace? Confused?, Suffering in silence? Feel disempowered?, Trapped? Are you wondering what conduct actually constitutes bullying, harassment or sexual harassment in the workplace? Do you need help determining whether you have grounds to lodge a claim?

If you are unsure whether you have a claim or which application you can pursue, please give us a call on 1800 333 666 for a free and confidential consultation. We are not sexual harassment lawyers, but one of Australia’s leading workplace advisors. We have been representing employees in sexual harassment claims since 2004. There are various decisions referred to and set out below you can read to get a better understanding as well. We work in all states, including Victoria, NSW, QLD, cities of Melbourne, Sydney, wherever call us. Fair work commission matters, including forced to resign due to sexual harassment, stop sexual harassment order, dismissed for complaining about sexual harassment.

Citations

[1] Thiess Pty Limited v Industrial Court of New South Wales [2010] NSWCA 252 (30 September 2010) at paras 65–67, [78 NSWLR 94]; Abigroup Contractors Pty Limited v Workcover Authority of New South Wales (Inspector Maltby) [2004] NSWIRComm 270 (24 September 2004) at para. 58, [(2004) 135 IR 317].

[2] Re Ms SB [2014] FWC 2104 (Hampton C, 12 May 2014) at para. 45.

[3] Ibid.

[4] [2015] FWC 774.

[5] Ibid at para.99.

[6] Naidu v Group 4 Securitas Pty Ltd (2005) NSWSC 618 (24 June 2005).

[7] Ibid; Styles v Murray Meats Pty Ltd (Anti-Discrimination) [2005] VCAT 914 (12 May 2005).

[8] Naidu v Group 4 Securitas Pty Ltd (2005) NSWSC 618 (24 June 2005).

[9] Willett v State of Victoria [2013] VSCA 76 (12 April 2013).

[10] WorkCover Authority (NSW) (Inspector Maddaford) v Coleman [2004] NSWIRComm 317 (3 November 2004), [(2004) 138 IR 21].

[11] Willett v State of Victoria [2013] VSCA 76 (12 April 2013).

[12] Naidu v Group 4 Securitas Pty Ltd (2005) NSWSC 618 (24 June 2005).

[13] Thompson and Comcare [2012] AATA 752 (31 October 2012).

[14] Martinez and Comcare [2012] AATA 795 (14 November 2012).

[15] Truscott and Comcare [2012] AATA 220 (17 April 2012).

[16] Towns and Comcare [2011] AATA 92 (14 February 2011).

[17] State of Tasmania v Clifford [2011] TASSC 10 (24 February 2011).

[18] Towns and Comcare [2011] AATA 92 (14 February 2011).

[19] Drenth v Comcare [2012] FCAFC 86 (21 May 2012), [(2012) 128 ALD 1].

[20] Re Ms SB [2014] FWC 2104 (Hampton C, 12 May 2014) at para. 52.

[21] Keen v Workers Rehabilitation & Compensation Corporation [1998] SASC 6519 (25 February 1998), [(1998) 71 SASR 42]; Re Ms SB [2014] FWC 2104 (Hampton C, 12 May 2014) at para. 52.

[22] Amie Mac v Bank of Queensland Limited and Others [2015] FWC 774 (Hatcher VP, 13 February 2015) at para. 102.